The supermarket business in the U.S. Heartland remains “strong and vibrant,” said Anthony Totta, CEO at FreshXperts LLC, Kansas City, Mo.

The industry saw a surge in business when COVID-19 hit in March, and though sales have leveled off a bit, they remain higher than pre-pandemic numbers, he said.

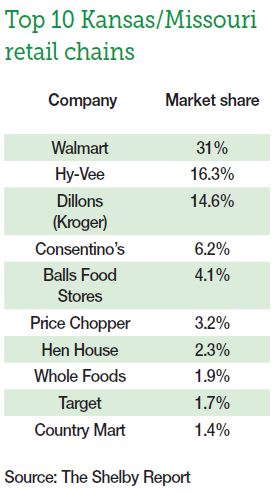

The Shelby Report lists Walmart in the No. 1 spot among retailers in the Kansas/Missouri region with about 31% of the market.

Hy-Vee is second with 16.3%, followed by Dillons (Kroger) with 14.6%. About 20 other chains are represented, all with less than 7% market share.

A large piece of the retail pie consists of stores supplied by Kansas City, Kan.-based Associated Wholesale Grocers Inc.

Those banners include Sun Fresh, Price Chopper Supermarkets, Country Mart, Apple Market and Thriftway Supermarkets, Totta said.

“I think the independents supplied by Associated Wholesale Grocers probably have the biggest slice of the market share, followed by Hy-Vee,” he said.

Employee-owned Hy-Vee apparently sent shock waves through the Kansas City metropolitan area when it arrived there around 1988.

Other major chains had tried to penetrate the market but eventually were run out, Totta said.

Within 10 years, Hy-Vee grew to 20-plus stores, and there now probably are 30 Hy-Vee locations in the region, he said.

“They took quite a bit of market share from the Price Chopper group, which was the dominant group for a long time,” he said.

“(Competitors) underestimated Hy-Vee,” he said.

The differentiating factor is the Hy-Vee business model, Totta said, which enables department heads to work on a commission-only basis.

“They become like a bunch of small businesses within a business,” he said. “Each department head treats the customers like their life depends on it, because their income depends on it.”

The stores are run like a blend of a chain and an independent market.

“Before anyone knew what hit them, they were able to have a foothold here,” he said.

Read more about produce retail here.

They spent money to establish themselves, including sponsoring Kansas City Chiefs football.

“They've come to stay,” Totta said.

But one recent business decision fizzled.

Hy-Vee established four fulfillment centers for online ordering, including a 136,000-square-foot facility that opened last fall in Kansas City, Mo.

A few months later, it announced that it was closing all of the centers, including locations in Kansas City; Eagan, Minn.; Des Moines, Iowa; and Omaha, Neb.

“They're showing signs of being stressed,” Totta said. “Maybe too rapidly grabbing of market share.”

In the past four years, Trader Joe's and Sprouts also have gained a foothold in the area, and Aldi has expanded.

“Trader Joe's and Aldi's have a nice chunk of the business now,” Totta said, but deep discounter Save-A-Lot is

“struggling to survive in this market.”

Produce plays an important role in Heartland markets, he said, taking up a spot near the entrance of most stores.

There's good reason for that.

“They add approximately 30% to the bottom line of a store,” Totta said. “Stores that do well in produce succeed, and those that don't make a priority out of produce struggle.”

A factor setting the Heartland market aside from many others is the large number of independent stores, Totta said.

“Our area is dominated by independents,” he said. “That's the biggest difference.”

There are strengths and weaknesses that come with both formats.

Chains have some disciplines that independents lack, he said, and they have alternative sources of funding that can keep stores open.

But independents can mold their operations to the shoppers they serve, and they're not as prone to “manage by analytics and business intelligence as chains do from ivory towers,” he said.

Totta comes from a family of independent grocers, and he said he still is acquainted with many of them.

“They are fiercely independent and they're survivors,” he said.

Associated Wholesale Grocers has been “a powerhouse” in the region, supplying 3,500 markets, he said.

The company is set up as a co-op, with retailers as shareholders who share in the bottom line.

“(Associated Wholesale Grocers) gives annual rebate checks that help strengthen the independent retailers,” he said.

Even though they're supplied from the same source, the banners set up their own ads, and consumers benefit from the competition, he said.

“The food prices are held down pretty low.”

Most area produce departments carry a wide variety of items, he said, including locally grown bell peppers, tomatoes, squashes and some fresh herbs.

As in other regions, Heartland consumers have taken to online ordering for curbside pickup or delivery.

Totta thinks that's a practice that is here to stay.

“It's going to continue to mature and refine,” he said.

Get to know the Heartland market better.

Part of that process will be a change in the pricing structure, he believes.

“Unless they start charging for the delivery and charging for the service of selecting orders, they cannot make money,” he said.

“They can't make money because grocery stores don't have that much margin built in to overcome the labor of doing personal shoppers shopping for people and providing that service.”

Charging the same price online as for products on the shelf is not sustainable, he said.

“They have to charge something above what they have on their shelf,” Totta said. “If they don't, they're losing money.”