Regardless of a muggy August, every day inside the quarter-mile-long Philadelphia Wholesale Produce Market is like a chilly October stroll, but you'll need to keep an eye out for hand truck drivers weaving around with cartons of product for retailers or restaurants.

The difference this year?

The market and its firms are experiencing a new partnership in sustainability, more deliveries and increasing use of imports.

Gate traffic and floor traffic has been heavy, a good sign of overall business, Mark Smith, president and general manager of the market.

“Everyone is just trying to find good labor and good help. That's probably one of our biggest challenges as far as the market and businesses,” he said. “Obviously there was challenge getting pallets for a while, but internally we have a process in place for people who need them to get them. It seems to have worked out OK.”

Shop Rite is the No. 1 retailer so far in 2021, with a market share of 17.44% in the eastern Pennsylvania region, including Philadelphia and parts of New Jersey and Delaware, according to Shelby market data.

Acme had 14.05% market share; Giant Food Stores, 13.88%; Walmart, 11.01%; and Weis Markets, 7.05%.

Wasting less, feeding more

Reducing waste continues to be a top priority, but now a new partnership with nonprofit Sharing Excess is streamlining the process, Smith said.

“We're trying to get every edible piece of produce out to people who need it. That's one of our biggest efforts this year, trying to get that organized. That really helps the community and helps our waste stream as well,” Smith said.

Since Sharing Excess established its spot in Breezeway I, there's an even more refined sorting and distribution system for that tiny bit of edible food that typically goes to waste when not sold for whatever reason.

“We sort it, track it for deduction purposes, and we distribute it with the major food banks that already were picking up here, and for others, we'll deliver it if they need us to,” said Evan Ehlers, founder of Sharing Excess. He launched the program in 2018 with college student volunteers, first as a way to use unspent meal cards at Drexel University.

The nonprofit group's first retail partner was Trader Joe's and has since grown to about 40 retail stores and restaurants, and since June, the market's wholesalers too.

By the first week of August, Sharing Excess had delivered 3.2 million pounds of food to local hunger organizations since its founding, and 2.4 million pounds of that was in 2021 alone, Ehlers said. In less than two months, the organization has donated more than 350,000 pounds of food from the wholesale market.

Wasting edible food is a logistical problem.

“It's the inevitable nature of inventory and unpredictability of sales. It's this never-ending biological clock, and it will perish whether it's sold or not, and we're happy to place that small percentage that doesn't get sold. Of course, most vendors do sell most of their product,” Ehlers said.

With this onsite system, the excess food can be turned around fast: in 12 to 24 hours, that unsellable carrot bunch can be in the refrigerator of someone who really needs it but can't afford it.

Philadelphia is one of the biggest, poorest cities in the U.S., where one in five people face food insecurity, he said.

“When you have a dependable source for food from one place like this wholesale market, it's such a community benefit,” Ehlers said. “They're doing something that if every wholesale market did this in the country, the world would be a better place.”

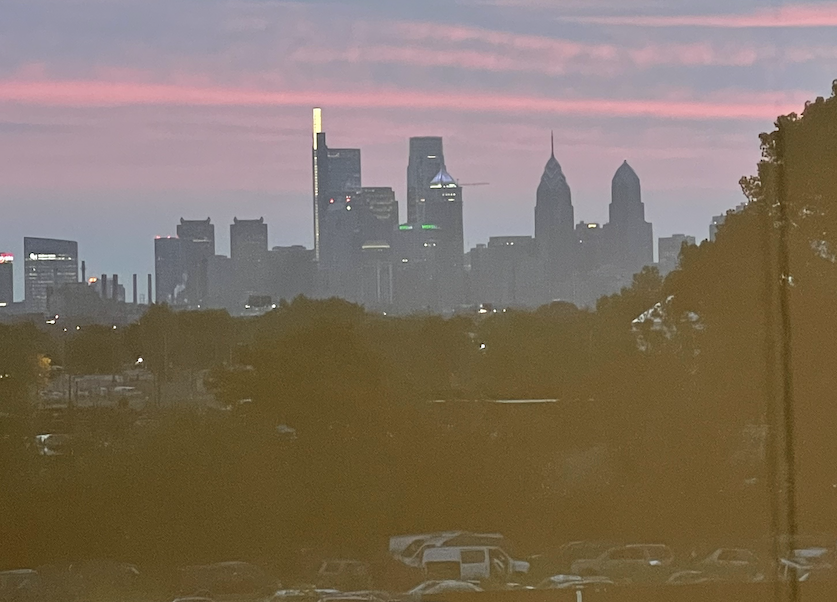

This is the view of downtown Philadelphia as seen from the Philadelphia Wholesale Produce Market.

Delivering

COVID-19 or not, Philadelphia needs the same amount of food whether it comes from retail or foodservice sources, said Filindo Colace, vice president of operations at Ryeco at the market.

“But what we do know for certain is that amount of customers wanting deliveries has increased, whether it's wholesale or retail. People want to stay in their buildings,” Colace said.

“It costs us more, but that's OK, we'll give up a little margin to keep selling the produce.”

Fewer people want to physically go to the market themselves.

When Colace started working at Ryeco six years ago, the company had no delivery trucks. Now, Ryeco has 21 trucks, and with outsourcing, there are about 25 trucks out on the road daily, he said.

The younger generation leading these buyer decisions doesn't want to spend four hours at the market plus 10 hours back at the store each day like their parents and grandparents did, he said. But also, they want to be on hand at their own businesses, to manage employees and customers and maximize their own customer service.

“We have to adapt to what the market wants,” Colace said. “I don't think COVID changed the trajectory. I just think it made it go faster for some people.”

Companies have been adjusting however they can, while supplies are unpredictable and demand fluctuates wildly.

“Our buyers and sales team are on overdrive to serve our customers as best we can – but we expect this instability to continue well into 2022, at least,” said John Vena, president, and Emily Kohlhas, director of marketing, at John Vena Inc., based at the market. “The best we can hope for right now is that we all continue to face to unanticipated gaps and gluts with equanimity.”

Imports

John Vena is seeing a lot of growth in its imports division.

“Currently all units on the market are occupied, which is a great thing, but the growth of JVI Repacking and JVI Imports, our import division, is putting pressure on our capacity, and we are beginning to look forward to what might be down the pike,” Vena said.

The company's ongoing program of directly importing Israeli citrus during the winter and spring season will continue with Sunrise grapefruits, Sweeties and Orri mandarins.

Those imported grapefruits and Sweeties will be packed with GS1 DataBar stickers, an enhancement for traceability, said Dan Vena, director of sales.

The DataBar is a stacked omnidirectional barcode created by the global standards organization GS1, designed to fit on small, loose produce items too small for a UPC barcode, according to Produce Marketing Association.

While those import volumes look promising, Orri production is expected to be lower in 2022 compared to 2021, “due to excessive heat that the growing region has been experiencing,” Dan Vena said.

Ryeco is also doing a lot more direct importing than it used to do. The company received its import license and started this program in a small way in 2019.

“And it's really picked up in the last year — especially pineapples, clementines, mandarins, lemons, dragon fruit, oranges, pears and apples,” Colace said. “There's just demand for it.”

Besides the fact that some of those items — like pineapples and bananas — aren't grown commercially in a big way within the U.S., the cost of shipping produce from the West Coast has skyrocketed.

“We're getting it from the port in Philly, and we can pick it up with our own truck, and often at a better price. But not always.”