The Packer's Tom Karst visited in late April with Aidan Mouat, CEO and co-founder of Hazel

Technologies Inc., a Chicago-based agriscience company dedicated to extending the shelf life of fruits, vegetables, flowers and plants through responsible, sustainable chemistry products.

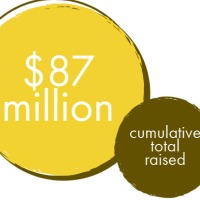

The company, founded in 2015, has recently finalized a $70 million Series C financing round, which will bring the company's cumulative total raised to over $87 million.

Hazel Technologies' flagship products deliver a controlled release of shelf-life enhancing vapor from packaging inserts called sachets. The sachets are placed in boxes of bulk produce by commercial growers at the time of harvest, extending the shelf-life of produce up to three times by slowing aging in produce and preventing decay, according to the company.

The Packer: Hazel Technologies recently had some big news recently with $70 million in series C financing announced. Since the founding of Hazel Technologies in 2015, how would you describe your journey so far?

Mouat: It's been a very interesting process. Myself, I am a first-time entrepreneur. Before this, I was just a chemist, and did my PhD at Northwestern. And it's a steep learning curve, a lot of new learnings almost every day, a lot of new tasks every year. I think that this most recent fundraise is really an extraordinary leap forward. We've always had a very capital-efficient perspective. And if you sort of look at our fundraising history, as a venture-backed ag tech business, up until this raise, over the course of about five years, give or take, we've raised about $17.5 million in a couple of rounds. And the goal was always to have good fundamentals, build out the platform, develop the technology, get in front of the customers, make sure that everything is working, and get to a stage where it makes sense to be able to accelerate growth in a very rapid way. And we developed a lot of confidence that's where we were. And of course, as a result, we decided to increase the degree of our fundraising and increase the impact it was going to have on the organization. It is a very exciting time for us. It is very fun to be in this sort of new paradigm of building our business, of globalizing our business, and really ramping up into our North American busy season, working more deeply with a lot of the same customers, a lot of new customers.

Meet Aidan Mouat, CEO and co-founder of Hazel Technologies Inc.; Photo courtesy Hazel Technologies Inc.

The Packer: Describe your commercialization so far. I know you are always bringing about new applications. How many commodities is your technology used with? Any estimates on the number of cartons or maybe millions of pounds that have been used with the technology?

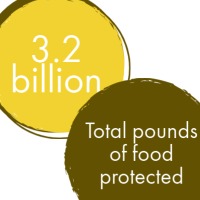

Mouat: As a sustainability-focused organization, we try to track our activity very closely so that we can report out on it. In 2020, we estimate that we protected about 3.2 billion pounds of food total.

There's not a small number by any means, but it's about 100 to 1,000-fold less than we want to be doing. And I think it's a really strong commercial milestone, but still at the relatively small end of the spectrum, all things considered. The reason you see all that output from us is that we are in a constant feedback cycle with our clients and our customers. That's how we develop new applications, new crops. Even within crops, you have to think about different genetics subsections, different cultivars; they have different responses. So far, we're active in about 15 different crop types. They really span the gamut everywhere from temperate to tropical, tree to perennial to annual. And (we are) moving into some interesting uses this year as well, with our first non-crop application. We're doing some development work to create a product to extend the shelf life of cut meats in the protein sector.

The Packer: We hear about the sachets that go into the boxes. Is that the predominant way that (Hazel) technology is applied to produce? Are there other ways that you also use the technology with produce?

Mouat: It's even a bit misleading to say, ‘Is the sachet the number one (delivery platform)?' because there's actually a number of different SKUs within that line. We have conventional and organic, we have different kinds of (ingredients) to go in different types of sachets, and then we even have different scales of sachets. There is a basic SKU to treat at the 50-pound box level, there's an SKU that treats the 300-pound box level, the 900-pound box level and so forth. I would say that actually is the most popular iteration of our product. And I think the reason is that having that input that can go directly into a packing line environment or into a field packing environment, without having to create a new kind of process, or put some new kinds of equipment in place, that's had a very, very positive reception from the majority of customers. I think it's kind of a one-size-fits-most type of product where you can get granular with the application and get all the benefits, but no real overhead expenses. Although I will caveat that by saying that as we move forward in the future, and we think about ways to reduce labor burden, and ways to integrate with more types of lines and more types of packing environments, I think that the sachet will continue to be very important. But I think we're also looking at direct packaging integrations where we can interface with high-throughput lines, where customers can use the technology already integrated with their packaging materials and not have to add a labor step. That's a pretty exciting way to develop.

The Packer: Is the material applied directly to the produce?

Mouat: It's an interesting question, because on the one hand, you could argue that the produce interacts with it directly. But on the other hand, there's no real application to the produce; we're actually treating the atmosphere. And that's true for everything, sachets, packaging materials, whatever it is; what we're doing is emitting active ingredients or controlling the presence of active ingredients in the atmosphere of the food. That, in turn, creates biofeedback with the produce that mimics, for example, the natural ethylene; you can argue that ethylene is applied to produce. Yeah, it's a gas though working in the environment.